In this case study, you’ll discover:

- How to give a campaign that’s already been rolled out a few times before a significant boost;

- How constraining customers can actually make them want to participate more;

- The different ways to unlock value and how to leverage them in your copy; and

- Why simple messaging combined with precisely applied solutions from behavioural economics can lead to a 56% increase in sales.

Problem: How to make an already sweet deal even sweeter?

Australia 2014. There’s a whiff of anticipation in the air at KFC’s headquarters. But only a slight one.

They’re about to launch the same seasonal campaign that’s been running for a couple of years now. It seems as though their customers are used to it – satiated, as they lick their fingers and smack their lips – they’ve just feasted on their fair share of one-dollar Aussie chips.

This is no accident but the result of a clever french fry coup conducted by a team of behavioural scientists and creatives. By the end of the promotion, the whole amount of sales of “one-dollar Aussie chips” in South Australia will have risen by 56%.

Could this all be simply because someone thought of a new way to describe the same deal? And in doing so, stirred something deep within the customers’ psyche – their innate sense of what a great deal is?

Who’s behind this success and what can they teach us about the way we perceive value?

Behavioural strategist, Sam Tatam from Ogilvy UK explains that there’s no magic potion involved in the recipe of this marketing campaign. What you will find, however, is a fair share of curiosity, science, and research topped with heaps of creativity.

The challenge Sam and his team at Ogilvy Australia faced revolved around how to make something already great feel grand.

How to unlock intangible value?

KFC asked Ogilvy’s team of experts to increase the intangible value around one of their products: $1.00 french fries.

“But we couldn’t change the product or the price, we could only change how people saw it. In order to bring the right ingredients into the mix, we looked at the literature and found 18 different principles from psychology most relevant to the perception of value within fast-moving consumer goods,” Sam points out.

These principles involve more broadly-known concepts like scarcity — if something becomes scarce, we fear we might miss out on it and so we value it more; loss aversion—we’re twice as motivated to avoid a loss as we are to receive a gain; and social norming—if a lot of people are doing something, others see that it must be valuable, so they follow suit.

(Remember your mom asking you, “If your friends jumped off a bridge, would you?” whenever you asked her to buy you a pair of Lil Nas X Satan Shoes just because all your friends’ moms were buying them? No? Don’t remember? Oh, okay… awkward…)

But the team also explored more obscure behavioral principles and biases. For instance, a concept called value payoff—if something feels too good to be true, we start thinking: “Okay, what’s the catch?” and tend to look for the negatives. As Sam cheekily points out: “For instance, people might wonder, are those old potatoes?”

Companies can counter this worry by opening up about the negative aspects of a deal even before any concern pops up in the customer’s head.

For example, Ryanair justifies the lower price for their discount flights by asking passengers to pay for the food onboard. That way, it’s easier to make a direct connection between a lower price and no free bag of peanuts.

Excluding in-flight refreshments reinforces the idea that the value of the flight ticket was achieved by nixing this part of a standard flight package and not by cutting back on the plane’s engineering or the captain’s salary, which might actually be more scary and deter people from flying altogether.

But cutting back to the KFC problem; the team further explored which of the 18 different principles of psychology would work best in the context of one-dollar french fries.

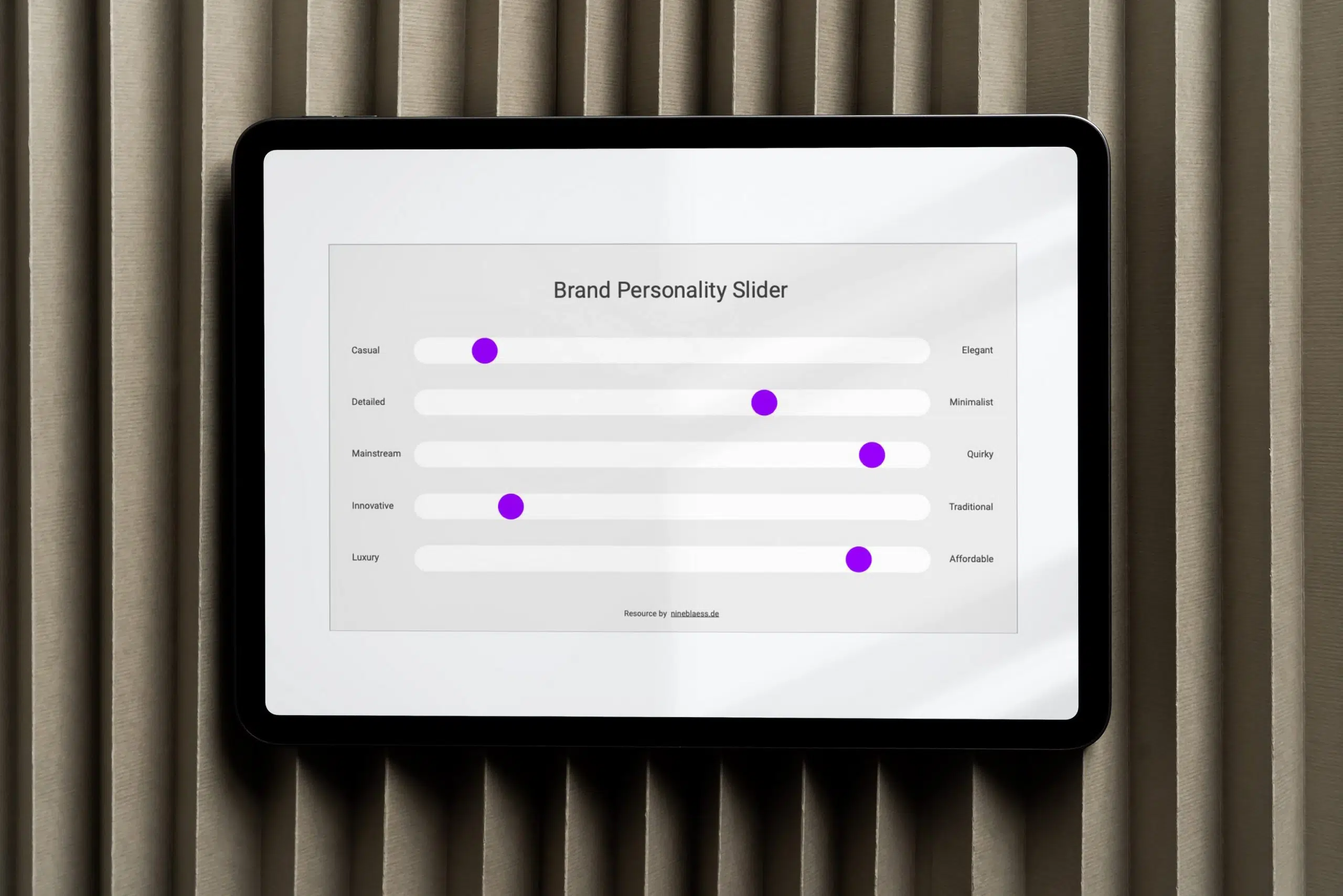

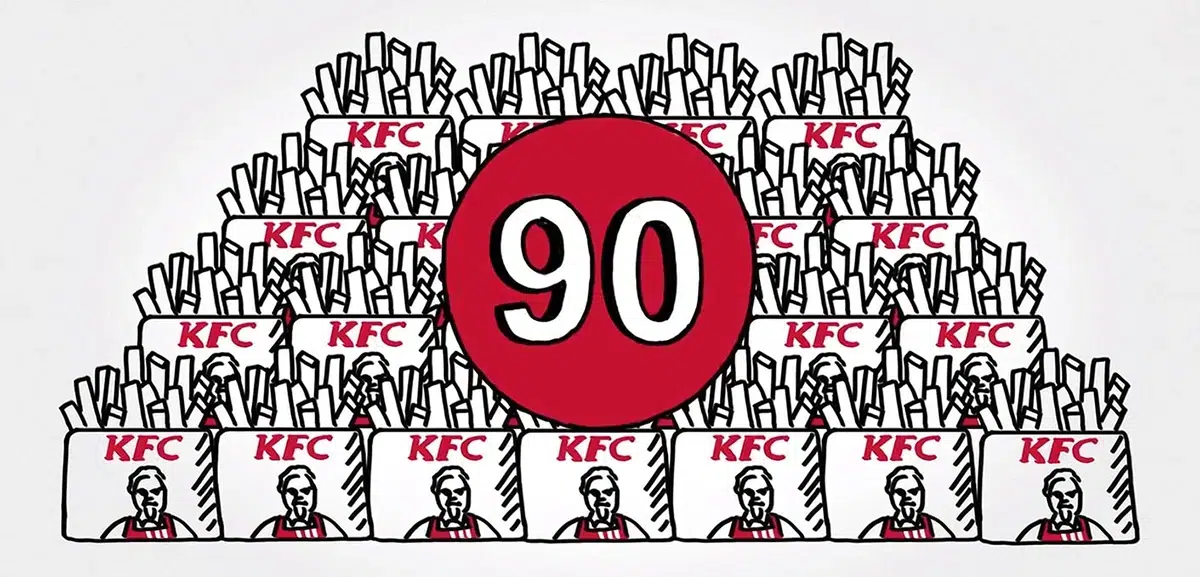

“We generated 90 different ways to say $1.00 french fries and cut them down to five core frames (messages) to test,” Sam explains.

5 different ways to say one-dollar french fries

1. Loss aversion

The first core message was designed to trigger loss aversion. It contained a timely constraint, which was vague enough to create uncertainty and encourage people to engage with the offer by generating a FOMO response.

No bells and whistles, it simply said:

“$1.00 french fries won’t be around forever.”

Notice that it didn’t specify when the deal would end. If it said the deal would be valid for the next 3 months, people might still feel like they had enough time, but this way they were not so sure. (Read more about loss aversion here)

Loss aversion

We are roughly 2.5 times more sensitive to losses than we are to gains of similar size

2. Reciprocity

Another frame used a principle known as “reciprocity” – if people do something for us, we feel inclined to return the favor. The Ogilvy behavioral experts team tapped further into a concept known as “reciprocal concession.”

“Imagine it’s like haggling at a market in Marrakesh; they start with 10 and you say 5 and then you meet in the middle at 7 – that’s a reciprocal concession. So we said:

‘You wanted free french fries, but we’ll meet you halfway with our french fries for $1,” concludes Sam as he shines more light on how Ogilvy pulled this off. (Read more about reciprocity here)

3. Value payoff

Recognising a limitation in the offer to reinforce the value was another interesting frame that the Ogilvy team tested out. This was achieved by leading in with the hook in order to reinforce the value with the message reading:

“$1.00 french fries – pickup only.”

“What’s really interesting about that particular frame is that KFC in Australia doesn’t do delivery anyway. And so we were basically just shining light on a fact, to reinforce the value of $1.00 french fries,” Sam reveals with a little twinkle in his eye.

4. Anchoring

Another frame to test was a quantity anchor. Anchoring was made popular by Dan Ariely; numerous studies have found that when companies introduce arbitrary constraints, people respond to it in curious ways. It makes them want it even more!

“By arming someone with an anchor, we can shape the perceived quantity that an individual should purchase,” Sam explains.

When Snickers bars offered a promotion that read: “Buy 18 bars for your freezer” instead of just saying buy some for your freezer, the average number of bars sold went from 1.4 bars to 2.6.

Similarly, Campbell’s soups started selling more when there was a limit of 12 cans per person. It went up from selling 3.3 cans on average (before the limit), to 7 cans after the limit had been introduced.

The idea—to bring a quantity anchor front and center—came naturally since one of the campaign disclaimers was “maximum four per customer.” “So rather than using the quantity disclaimer in the copy at the bottom of our ads, we turned it into our main headline,” Sam reveals.

“A deal so good you can only buy four”

5. Social norming

The final message tapped into the power of herd behavior, also known as social proof (for all those Cialdini fans out there).

It read:

“Everyone’s enjoying our french fries for $1, why not you?”, providing an example to follow a specific action many others find irresistible.

The process for generating the final propositions was the same regardless of the underlying principle.

“You start with converting theory into questions, which ultimately leads to final propositions. In case of social norming, it might be questions like: ‘how might we show customers that their friends are already consuming it? How might we show that many people have bought these french fries before?’ Answering questions like these would ultimately allow the creative team to come up with the final wording,” describes Sam.

A dry run on Facebook

The rate of unique clicks on sponsored social media posts were used as a proxy to access message potency. Consistent imagery was followed by five different articulations of the same message.

KFC tested each of these five conditions plus a control one over the course of a week to see which one got the greatest response rate measured by unique clicks data – they observed what engaged people and stopped them in their tracks to think about the offer.

Researchers found that reciprocity and anchoring significantly outperformed the control, whereas social norming performed significantly below.

As Sam further points out: “Anchoring changed the conversation from a price point – people talking about one dollar – into: Actually, how many can I buy? And if I go through the drive-thru twice, can I get six? So the simple use of psychology changed the conversation completely!”

On the other hand, the social norming message, which went backwards from the control, may have felt like advertising and people could smell that, and so it may have had an adverse effect.

This illustrates an important point. Behavioral science isn’t a silver bullet. But by testing and learning, we can understand what strategies are most effective and we can replicate and scale that accordingly.

Which is what Sam’s team ultimately did when they took anchoring insight into creative teams and developed a radio campaign for South Australia.

A 56% increase in sales

A subsequent radio and visual campaign resulted in a 56% increase in total french fry sales compared to the previous year. But it gets even more interesting when you look at where some of the sales were generated, the company saw an 84% uplift in 4 french fry transactions.

A different anchor led to a massive change in behavior, which drove a new kind of action not getting just 1 or 2 packs, but 4 instead.

Why? To borrow a famous retort from Mallory when he was asked the same question: “Why did you want to climb Mount Everest?” – “Because it’s there!”

Key takeaways:

- Treat every new campaign as market research to inform you of your future decisions. There’s no need to go all-in on the first try. Identify a proxy to assess message potency and start by testing out universal principles to see what performs better.

- Don’t be afraid to use theory as a starting point. Theoretical concepts may feel heavy, so think of ways to use these principles as a basis for generating questions that will allow you to come up with mini propositions and ultimately to final messaging. Some concepts will translate more easily and some won’t, and that’s OK.

- Be ready to embrace seemingly illogical solutions. For example, if you introduce a little hindrance or limit people’s choice by scarcity or anchoring just like KFC, you can drive action you’d like to see more of.

Case study by Sam Tatam, Head of Behavioural Science, Ogilvy Growth & Innovation